What Does a Scientist Look Like?

A bestselling book for middle schoolers answers this question in 50 ways. In honor of Women’s History Month, share a copy with a girl you love.

by Sue Tomchin

Ask a class of seventh graders to draw a picture of a scientist and most would probably show a bespectacled white male with an Einstein mane holding aloft a test tube or gazing into the lens of a microscope.

Male-focused stereotypes about who can become a successful scientist can dampen the dreams of girls with STEM potential. Just look at this pertinent stat: The 2011 census showed a 52 percent gender gap in the STEM workforce.

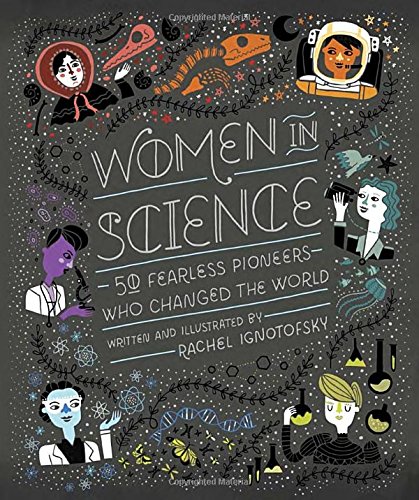

Author/illustrator Rachel Ignotofsky has channeled her passion about dispelling stereotypes and encouraging girls to pursue STEM studies into a bestselling book, Women in Science: 50 Fearless Pioneers Who Changed the World. While geared to a middle school audience, the rest of us will also enjoy learning about the striking contributions of trailblazers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

“The women in this book had to fight these stereotypes to have the careers they wanted,” writes Ignotofsky. “They broke rules, published under pseudonyms, and worked for the love of learning alone. When others doubted their abilities, they had to believe in themselves.”

Just out on March 7 is a companion to the book—Ignotofsky’s I Love Science: A Journal for Self- Discovery and Big Ideas. This guided journal features plenty of space to ponder and plan plus inspirational quotes from female scientists and infographics such as a star chart and the periodic table of elements, all presented in the author’s imaginative style.

Reprinted with permission from Women in Science Copyright © 2016 by Rachel Ignotofsky. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of

Penguin Random House LLC.

While there have been many books highlighting outstanding women in history, Women in Science conveys an energy that I found irresistible. Ignatofsky has a knack for presenting potentially dense information in a fun and accessible way. Accompanying compelling one-page bios about each woman is a playful portrait and other drawings that highlight striking facts about her life and accomplishments. Did you know, for example, that 19th century mathematician Ada Lovelace was the first person to create a computer program? That biochemist Dorothy Hodgkin figured out the molecular structure of penicillin, setting the stage for its manufacture, thus saving millions of lives? That Hollywood movie star Hedy Lamarr, called “the most beautiful woman in the world,” developed a technique that is now used in WI-FI, Blue Tooth and military communications? Or that now-famous primatologist Jane Goodall was inspired by the book Tarzan to go to Africa, working as a waitress and production assistant on documentaries to fund her first trip there?

What comes through loud and clear in the story of these women’s lives is the importance of perseverance and commitment to one’s work and vision, despite obstacles and setbacks. In other words: It takes grit to work as a woman in science, but don’t give up. Here are just a few examples of what the women faced:

- Florence Bascom, who would go on to train almost every female geologist of her time, was the first woman to get a PhD at Johns Hopkins University, but was forced to take her classes from behind a screen so she wouldn’t “distract” male students;

- Mathematician and theoretical physicist Emmy Noether, creator of the field of abstract algebra, worked seven years at the University of Gottingen in Germany without pay because she was female, and was later forced to flee Germany because she was Jewish. In spite of this, she developed equations that are still an important part of how physics is understood today;

- Physicist Lise Meitner performed her radiochemistry work in a dank basement because women weren’t yet accepted at the institute in Berlin where she worked. After escaping from Germany in 1938, she continued her research, and went on to discover and explain the workings of nuclear fission, changing physics forever; and

- Rosalind Franklin took painstaking photos that ultimately proved that DNA is a double helix, yet her work was used without credit by scientists James Watson and Francis Crick in the groundbreaking paper they published. She went on to do critical work not only on DNA, but RNA, viruses and polio. Watson and Crick received the Nobel Prize after she died.

Lamarr, Noether, Meitner, and Franklin are four of at least a minyan of scientific pioneers of Jewish background that Ignotofsky features, making this book an inspiring gift for a bat mitzvah girl or a daughter, niece or friend with a flair for science or math.

The fact is, any girl with a questing spirit can’t help but draw strength from a hour or two spent in the company of these 50 women, “who in the face of ‘no’ said, ‘Try and stop me.’”