Women’s Suffrage Came at A Cost

This time next year, we could have a woman in the Oval Office. In this context, it’s hard to believe that just 100 years ago, women didn’t have the right to vote. In honor of Women’s Equality Day, JW Magazine went to Lorton, Va. to learn about the struggle for suffrage.

By Lauren Landau

According to the Pew Research Center, about as many millennials are eligible to vote as Baby Boomers. However, despite the potential power of this young generation, millennials “have punched below their electoral weight in recent presidential elections.”

With another election looming in November, pollsters, pundits, and politicians are wondering: Will young people cast their ballots or stay away from the polls?. Whether they don’t like the candidates, don’t believe their vote matters (it does!), or just don’t care about politics, some people choose not to vote. Be it as protest or from passivity, voter turnout is never what it could be.

Through its #VoteLikeAGirl campaign, JWI aims to impress the importance of voting upon the electorate. It is particularly important that women participate, and not just because of the numerous issues that directly affect them. Like the right to access birth control, have her own credit card, and start a family without fearing the loss of her job, women’s right to vote was fought for and won.

This Women’s Equality Day marks the 96th anniversary of the 19th Amendment’s certification. Women have come a long way since securing their right to vote, and while issues of inequality still persist, the successes are so many that some Americans apparently don’t realize half the population was once barred from voting.

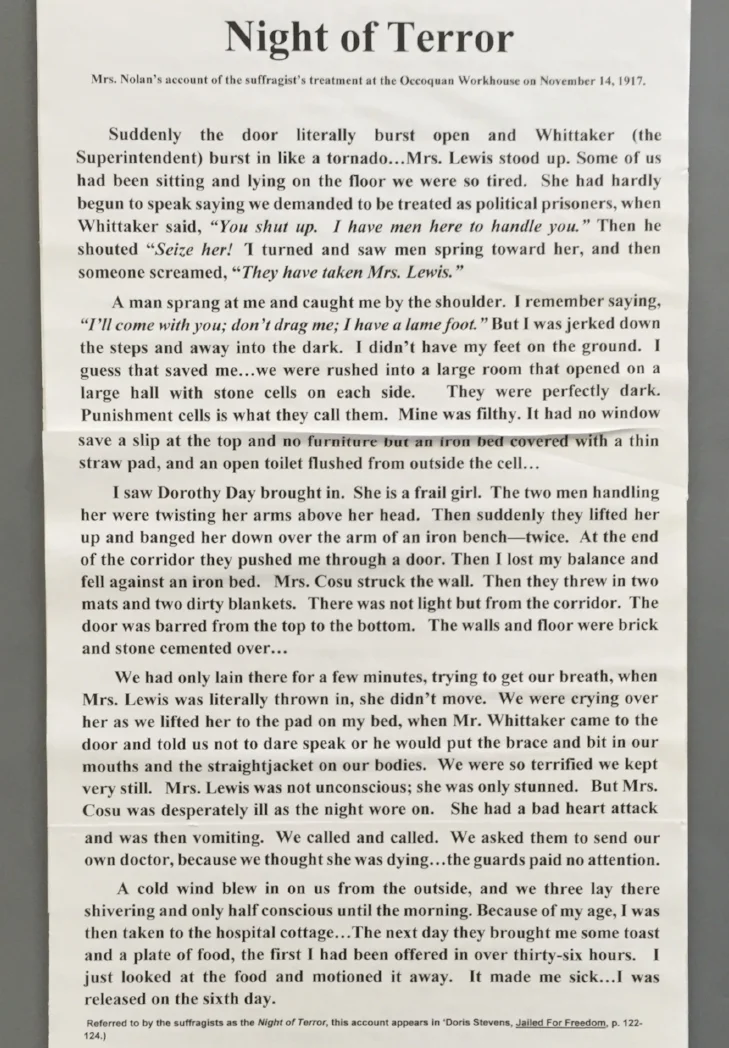

"Night of Terror," Mrs. Nolan's account of the suffragists' treatment at the Occoquan Workhouse on November 14, 1917.

Laura McKie, chair of the Workhouse Prison Museum and History Committee, speaks to visitors, including schoolchildren, about the history of the facility in Lorton, Virginia. Until the prison closed in 2001, it housed inmates from Washington, D.C. In the summer and fall of 1917, 72 of those inmates were members of the women’s suffrage movement.

McKie says that many of the teenagers and children she speaks to have no idea that at one point, women couldn’t vote. “These kids are growing up in a time when women are having more and more important jobs, where we have a woman, for heaven’s sake, running for the presidency of the United States, and to think that 100 years ago, a woman couldn’t even vote,” she says. “This is something that boys need to know as well as girls.”

A permanent exhibit at Workhouse Arts Center tells the story of the suffragists who were imprisoned for demanding their right to vote. Specifically, they were charged with obstructing free passage of the sidewalk in front of The White House.

“For that they were first fined, then jailed, and eventually sent down to the workhouse in Lorton for a six-month sentence,” McKie says. Incarcerated alongside the prison’s usual population—primarily prostitutes and vagrants—these middle and upper-class women were forced to wear prison clothes and work, but that was hardly the worst of their treatment.

“Some of the women felt that they were political prisoners and should be treated as such, so they went on hunger strikes,” McKie says. “During those hunger strikes, the superintendent felt that it was improper to have someone die during their imprisonment here, so he ordered that they be force-fed.”

Behind white iron bars, a diorama housed in a corner of the exhibit shows a slender figure in prison garb strapped to a chair with brown leather restraints. The woman is reclining, a rubber tube—and a dribble of blood—runs out of her nose. A mustachioed male figure looks on while a prim and proper female attendant holds a funnel aloft, keeping the caloric concoction moving smoothly through the feeding tube.

It does not look comfortable, and as McKie explains, it wasn’t. In order to be force fed, she says, prisoners would be strapped to the chair. Sometimes it took as many as four men to hold a woman down for the process.

“The tube went down her nose and then raw eggs and milk were poured directly into her stomach,” McKie says. “Those women who have written about the experience afterward speak of the pain—this felt like a ball of lead in the stomach, and of course there was pain in the nose from the tube going down.”

Hunger strikers endured this painful process three times a day. As McKie notes, no one died in the prison, but their experiences were traumatic enough to write about later. Thanks to those documents, historians know what these women went through in the name of suffrage.

The art of paying tribute

Much has changed since 1917. Lorton isn’t a prison anymore. The grounds now house the Workhouse Arts Center, where visitors can attend concerts, take a Zumba class, and visit artists’ studios. A current outdoor sculpture exhibit called Prison (Re)Form takes visitors on a walking tour of the grounds, learning about its history.

Dalya Luttwak, In Memory of the Suffragists Here Imprisoned, steel and paint on historic guard tower, 2016

Two Israeli artists, Dalya Luttwak and Sassona Norton, have created sculptures that pay homage to the memory of the women suffragists imprisoned at Lorton.

Just a short walk from the Workhouse Prison Museum, visitors find a guard tower surrounded with natural grasses and shrubs. However, some of the flora stands out from the rest. A hot pink steel “vine” climbs up the tower. Luttwak says she chose hot pink for In Memory of the Suffragists Here Imprisoned to highlight the power of the Suffragist movement.

Luttwak has exhibited her root system sculptures all over the world. “When my work is at its best, it’s site-specific,” she says. When Brett Johnson, director of visual arts at the Workhouse Art Center, approached her to turn the guard tower into a work of art, she immediately agreed.

“When Brett was telling me about the history and he mentioned the suffragists, I said I had to do something in their honor,” Luttwak says. “I wanted to do something substantial, but I didn’t want it to take over. [The suffragists] were here for a short time; there were not too many of them, and women can vote today.”

She wanted delicate “roots” that people would notice, but she didn’t want the work to consume the tower. The result is an installation that motorists can see from the nearby highway, but is subtle nonetheless.

The parallels to women’s suffrage are appropriate. The history of what these women endured is well-documented and easy enough to uncover, yet many people don’t take the time to learn about or recognize it.

Luttwak says she was shocked when she learned about what happened here. “I did not know about it,” the Maryland resident says. “I did know about the British [suffragists], but I didn’t know about the fight here and that it’s so close to where I am.”

“In America, to be imprisoned for [demanding] the right [to vote]? There’s a discrepancy here between the American ideal and what was being practiced, even 100 years ago,” she says.

Like roots fighting to break through a sidewalk, the suffragists refused to be silenced. They emerged strong and victorious, but it was a difficult battle. In An Hour Before Dawn, Norton focuses on the emotional element of the struggle for suffrage.

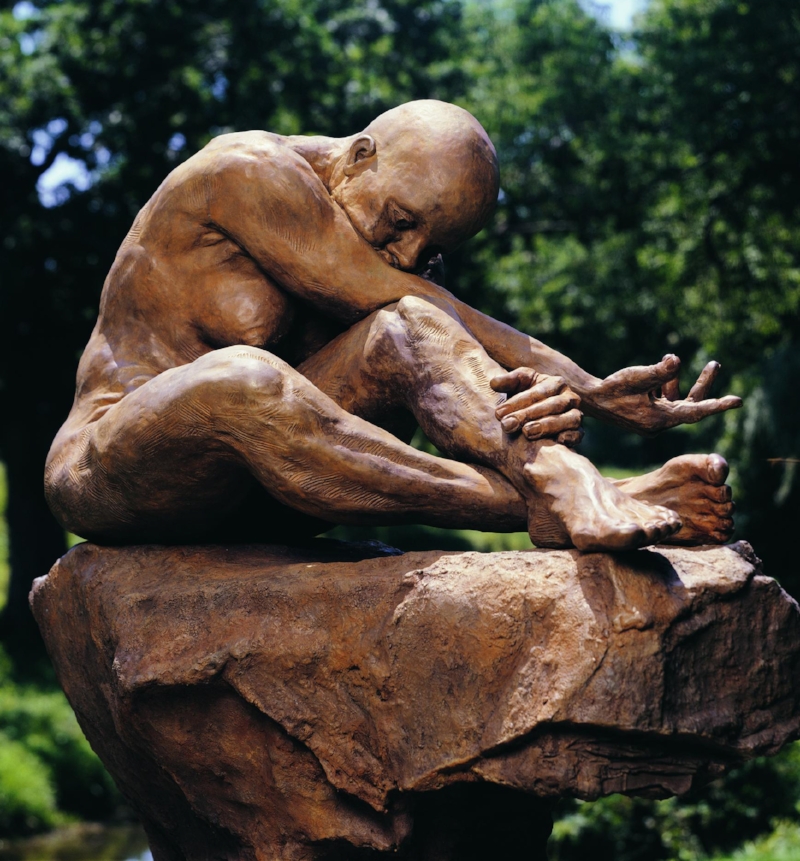

The bronze sculpture is striking. A bald and naked woman sits on a rock, her legs crossed at the ankles as she gnaws at the inner elbow of an outstretched hand. Her eyes are wide and vacuous, portraying the sadness and the fear that accompanies being powerless.

“While one arm of the woman embraces the body closely and intimately, the other is stretched forward over the empty space to reach out,” Norton says in her artist’s statement. “The contradiction is agonizing and the woman’s lips are closing on her arm. The feeling of unrest is carried by the dichotomy between the fragility of the movement and the certainty that is expressed in the overall muscularity. It is a dialogue between vulnerability and strength.”

Sassona Norton, An Hour Before Dawn, bronze, 2001

She says the desire for a better life is rooted in women’s “emotional DNA.” But the race toward that goal has not been easy.

“Society, controlled by men, trusted [women] with family lives but deprived them from having any power outside the home,” Norton says. “Having no voting meant that women had no say in the direction that society took, and that they were stuck in a life with no prospect of change. It made yearning powerless and life unbearable.”

Johnson says that yearning reflected in the sculpture is precisely what the suffragists did. “When they were here, they suffered, they were tortured, force fed, and this piece sort of speaks to that,” he says.

“It also happens to be looking in the original direction of where the suffragists were kept.” Once just across the road, the wood Occoquan Workhouse has been replaced by county-owned buildings.

The best way to say “thank you” is to vote

Voting, Norton says, is true power. “In this year’s elections, the fight for the future may take a regretful and an irreversible turn,” she says. “We must have our voice heard. We owe it to our past and to our future. We owe it to ourselves.”

McKie agrees. She says when the suffragists were imprisoned at Lorton, and people learned about their treatment there, there was a turning point in public opinion about women demanding the right to vote.

“Up to this time, from the very beginning, women had asked for the right to vote,” she says. “But with this new breed of women at the turn of the century, they demanded the right to vote.”

McKie believes that young women must learn about this history so that they can realize the sacrifices that were made to get the vote. “These ladies were willing to go to jail for their total commitment to women having the right to vote, to be equal to men.”