Creature Comforters

Rescuing animals is only the beginning for the women behind these innovative and compassionate programs.

by Sue Tomchin

I believe we haven't lived life until we have hugged a cow,” says Ellie Laks, shown hugging Buttercup, “a Jersey cow with a sweet and loving energy that makes everything better.”

On a hot day in the San Fernando Valley near Los Angeles, Ellie Laks was out and about doing errands with her infant son, Jesse, strapped in his car seat, when she spotted a run-down looking petting zoo surrounded by a chain link fence. Always an animal lover, she parked, put her son in his baby sling, and walked inside. What she saw shocked and disturbed her deeply – listless pigs standing in accumulated excrement, a llama with a matted coat, an ill-looking goat with a distended belly, exhausted ponies being forced to give rides to children. Despite the heat, no drinking water was visible and the air was fetid.

By the time she left she had resolved to help. She ultimately adopted many of the facility's animals and nursed them back to health. Thus was born her life’s work: The Gentle Barn, a unique sanctuary outside of Los Angeles.

Michele Raffin had never handled a bird before when she picked up the wounded body of a white dove by the side of the highway and tried to save it. That act inspired her to shift the direction of her life and to found Pandemonium Aviaries in Los Altos, Calif.

Pets are a growing presence in American life. Sixty-eight percent of households own a pet (American Veterinary Medical Association), and 9 out of 10 pet owners say that they consider their pet to be a member of the family (Harris Polls). Laks and Raffin, both passionate pet owners, were moved to take their affinity for animals into new territory, creating programs that benefit individual animals, but also have outcomes affecting the larger world.

FInding Safety with Animals

“One of the reasons I probably identify with animals so much is that I understand that feeling of being overpowered, of being dominated, of having no voice, having no rights, not being seen as the beautiful being that you are,” says Ellie Laks, in a phone interview.

Born in Israel into an Orthodox family (her grandfather was the chief rabbi of South Africa), she came to the U.S. when she was a young child. Her early affinity with animals was neither understood nor appreciated.

“In the Orthodox community in which I grew up you were not supposed to go crazy for animals,” Laks says. “You were supposed to dress a certain way and act a certain way. There was this idea of normal that I didn’t fit into. In the human world I felt there was something off about me or at least that was the mirror I got from other people,” she recalls. “With animals, I felt safe, not judged, and could be who I am.”

In her memoir, My Gentle Barn: Creating a Sanctuary Where Animals Heal and Children Learn to Hope, she relates that male baby sitters sexually abused her as a young child. And then, at age seven, a man approached her when she was playing at the lake near her St. Louis home. “I’d been taught by the babysitters to say yes and wait patiently until it was over. So that’s what I did with this man,” she writes. When she told her parents, her father blamed her and her mother dismissed her concerns, though they did stop hiring male babysitters.

"We used the interactions with Sasha to practice [Zach's] mobility... We put carrots in his hand and used the feeding process to exercise his right arm. By the time he graduated our program, he had full mobility in that arm. And he would laugh, smile and talk to us using his eyelashes.... His life changed."

Simon, Lak’s Australian shepherd, was a constant companion, but there were also a series of hamsters, bunnies, birds and other small creatures she either picked out as birthday gifts at the pet store or brought home from the woods to nurse back to health. Her mother, burdened with caring for her and her brothers since her father worked long hours as a cardiac surgeon, would “grow tired of them, and the animals would be gone.”

After one of these disappearances, Laks screamed at her mom: “When I grow up I’ll have a huge place filled with animals and they’ll be my friends. I’ll show the world how beautiful they are.” She clung to this dream through the ensuing years, even in her twenties when she had to pull herself out of the grips of a cocaine addiction.

A few months after her visit to the petting zoo, when she looked out of her window and saw the menagerie of rescues filling her yard and barn, she realized her dream had come to life. The Gentle Barn, her program, was born.

First alone, and then with the help of her second husband, Jay, she took care of a growing number of unwanted animals – including goats, chickens, pigs, cows and horses.

“We were rescuing animals, healing them, building barns, building fences, planting trees,” she said. ”We did all the work ourselves. We didn’t take a vacation for the first ten years. Everything we did, we dedicated to our purpose. Our kids did it with us. It was a seven day a week thing. But when you are living your dream, you don’t feel like you are working because you are doing what you love.”

Now the Gentle Barn has 173 animals, a staff of 12 and 900 volunteers. “If people are moving and have pets they no longer want to keep, we refer them to other agencies,” Laks explains. “We only take in animals that other adoption agencies won’t take in, rehabilitate them, and typically they stay here for the rest of their lives.”

Once the animals are well, they help with the Gentle Barn’s other work: to heal children, seniors, veterans, women from domestic violence shelters, and others who are isolated, neglected or abused.

A group of young people from the projects in South Los Angeles, for example, has been coming for years. “In the projects, you’re lucky if you see a tree amidst the concrete, barbed wire and brick,” Laks says. “There’s poverty, drugs and gangs and it’s easy for kids growing up there to think that is all there is to life. At the Gentle Barn, we show them open spaces and the colors of nature. They garden and grow real fruit and vegetables that they are able to take home. When they hug a cow, give a pig a tummy rub and cuddle with a turkey they are able to see something so different from where they live and begin to understand that the world is full of possibilities.”

One visitor whom Laks will never forget is Zach. A quadriplegic, he could bat his eyelashes and smile, but couldn’t talk and only had small movements in his right hand. No one recognized that there was intelligence trapped behind his disabilities. “At home, his family popped him in front of the television and in the classroom they parked him in a corner.” When his class of special needs high school students came to the Gentle Barn, everyone was given a project, but Zach was wheeled off to the side. “I said, ‘Absolutely not, he’s got to participate too.’ I brought Sasha, one of our horses, over to meet him. Sasha is really kind and loving and very beautiful. Zach couldn’t reach out to her, but she reached out to him: She started grooming him, using her lips; she groomed his head, cheeks and shoulders. At first his eyes were closed, because he was so used to not engaging with anyone that he hid in his own mind. She kept working on him, and eventually he opened his eyes and focused on her and started smiling and laughing and fully came to life. It was amazing.”

“We used the interactions with Sasha to practice his mobility,” Laks continues. “We put carrots in his hand and used the feeding process to exercise his right arm. By the time he graduated our program, he had full mobility in that arm. He would hold on to her bridle and we would push his wheelchair and he would feel like he was leading her. And he would laugh, smile and talk to us using his eyelashes.”

When the teachers and other students saw Zach interacting with the Gentle Barn animals and staff, their attitude toward him changed and he became a central part of the classroom. Everyone started talking with him and involving him in activities. And because the class was doing it, at home things changed too, and his family invited him to sit at the table.

“His life changed,” Laks says. “It took a horse to do it. Animals don’t have blinders on like we do. Sasha saw a being she wanted to interact with and she reached inside of him and pulled him out.”

Despite her childhood disaffection with Judaism, Laks now sees her work as intimately connected to Jewish teachings. “In my book I talk about how I didn’t relate to Orthodox Judaism. I had a hard time with it. Now that I am adult, I understand that kindness to animals is at the very core of Judaism. The very idea of kashrut is that we need to remember that animals are living beings and we can’t be so callous that we kill a baby and cook it in its mother’s milk. What I’m trying to do is to spread this kindness every day.”

For the Birds

Growing up in a close knit Conservative Jewish community in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Michele Raffin recalls that a Jewish teaching about animals made a strong impression on her. “I still remember being taught that a man feeds his livestock before he eats himself.” She was also fascinated with the story of Noah’s Ark, and the idea of rescuing animals and later even wrote an unpublished book about it.

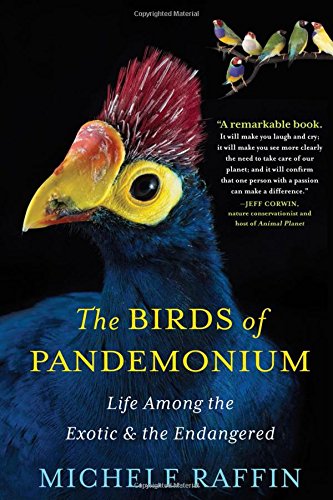

“As a toddler, my first friend was a puppy named Bow Wow. We crawled around together.” Later, as she recalls in her recent book, The Birds of Pandemonium: Life Among the Exotic and the Endangered, she became the “de facto animal rescue agent in our suburban San Juan neighborhood.”

When she went off to college in New England and later moved to the San Francisco Bay Area to work as a venture capital consultant in Silicon Valley, she volunteered at animal shelters.

“I’ve always felt a strong connection with animals, along with a deep revulsion for their suffering at human hands,” she writes. “The truth is I need them in my life. It’s a connection that settles and comforts me in a direct, non-judgmental way that people can’t often provide.

When she and her then-husband Tom, a physician, bought a house on an acre of land in Los Altos, there were always an array of dogs and cats about, along with their three young boys and her husband’s preteen daughter.

She had never held a bird before when, in 1996, she joined a health club and the trainer, who was supposed to give her a free training session, showed up late. He explained that he had seen an injured white dove on the side of the road and didn’t want to leave it. They drove together to check on it, and Raffin picked up the delicate body. They went in search of an avian veterinarian.

The bird didn’t survive, but Raffin had been affected by the experience. She was still moping when she saw an ad in the paper placed by someone who needed a home for a white dove. She ended up with six of them.

Today, Pandemonium Aviaries, her non-profit bird sanctuary and conservation organization, has more than 350 birds, representing more than 40 species. Her backyard landscape has gone from a single chicken coop to an ever expanding complex of aviaries, “thirty-four and still counting.” The garage is “now crammed with incubators, caged birds on ‘hospital watch’ and a few thousand live, homegrown mealworms.” And each morning she is treated to a symphony of bird calls.

Her life has changed in ways she could never have imagined. At the beginning she rose each day at 4:00 a.m. and worked incredibly hard, even on weekends. Feeding all the birds takes four hours. “My kitchen is filled with cases of papaya, blueberries, melon, grapes. We buy or are given seed by the pallet,” she writes. Now, she has paid staff and volunteers to look after the birds.

All of her knowledge about how to care for and breed the birds has been learned by her own observations or by consulting other aviculturists. She herself is a certified aviculturist and is now a regular consultant to zoos and other breeders.

Along the way, she’s also learned that being called “bird brain” is “actually a compliment because birds are very smart,” she says. “I know that ‘eating like a bird' is not a compliment because birds eat a lot.”

She also knows that birds have emotions. Amigo, an Amazon parrot whom she reluctantly adopted because her son bonded with him, still doesn’t like her, she says. “I think he is justified. I argued against getting Amigo in front of him and he listened the whole time and has never forgiven me.”

Though her days are vastly different from her earlier years as a Silicon Valley executive with a master’s in management science, “All of my business skills have contributed to my ability to build this organization,” she says. Her attitude, however, is vastly different. “I had to adapt my personality to my work. Animals who are wild choose whether to accept me. I had to be a person they could accept. I had to be someone trustworthy and reliable. I was a Type A when I was out in the business world, but now I can’t multitask. I have to pay attention and be in the present.”

Over the years, Raffin’s rescue work has coalesced with conservation and environmentalism. Though she has kept the birds she already had in her care, she has now left conventional rescue activities to others. She concentrates on breeding the Columbidae, a family of doves and pigeons. Their habitats in New Guinea are being decimated: rain forests are being cut down to make way for palm plantations to meet the growing demand for red palm oil, which is highly touted in the nutritional world. Raffin is working with six flagship species, and trying to build up a reservoir of biodiverse birds, so they can be used to repopulate the species in a protected habitat if they become extinct in the wild.

“We chose these species with great care. There are many other species that were endangered but we were limited in what we could do,” she says. “We hope to become a model of how this can be done.”

Pandemonium has the second-largest flock of Victoria crowned pigeons under conservation in the world. These elaborately plumed birds have “wonderful personalities,” Raffin says. At about a foot and half in length they are just a bit smaller than the dodo, their long-extinct relative. She has grown the flock, “bird by bird” with “hatchlings and acquisitions from breeders and zoos.”

“Doing something I think is so important has kept me young,” Raffin says. “It has brought me in contact with people who want to save a piece of the world. I get to focus on saving this little piece and doing it with integrity. Action is the antidote to despair.”

(Originally published in spring 2015)

Sue Tomchin is the editor of JW Magazine.

Life-Saver

Lori Pasternak’s innovative approach to veterinary surgery gives owners a financially manageable option when their pets need advanced procedures.

Lori Pasternak

A few years ago, it seemed the end was near for Harley, a 12-year-old Labrador retriever. He had an 18-pound tumor hanging from his side and could no longer get around. When his vet deemed him too old for surgery, his owners reluctantly scheduled the appointment to euthanize him the following week, wanting to spend one last weekend with their beloved pet.

In the interim, they saw a story on Good Morning America about vet Lori Pasternak and Helping Hands, her innovative veterinary practice in Richmond, Va. They brought Harley in for surgery and within two days he was up and around and able to walk upstairs for the first time in three years.

Pasternak’s business model at Helping Hands is unique: The practice is devoted exclusively to surgery, a skill that she enjoys and excels at. She offers surgery and teeth cleaning for pets at rates that are, in most cases, substantially below those of other vets, so pet owners have a financially manageable option and don’t have to resort to euthanasia. She’s able to keep her prices down because she keeps her overhead low and her volume high. (Prices are listed online so there are no surprises.)

“Veterinarians love me, because when they have clients who can’t afford a procedure, they can send them to me and know the pets will get the best quality care,” Pasternak says. “I get the pets through a crisis and then back into their regular vet’s care. It’s a win-win for everybody.”

Now, 60 percent of Helping Hands’ clients come from outside of Virginia. “When you are quoted $8,000 for a surgery in New York, and can have it done for less than $1,000 in Richmond, it’s worth the car ride,” she says.

Sometimes a client doesn’t have money available for surgery and an animal is in a life-threatening situation. Under those circumstances, Pasternak will do the surgery and the owner agrees to volunteer for a specified number of hours commensurate with the cost of the surgery.

“We’re not a non-profit,” she says. “The way we get the resources to do this is by charging everyone who uses our services an additional $5. Then we donate our time and the owner donates back to the animals in our community. We call it our merry-go-round of kindness.”

Thirty years ago, Nina Natelson was appalled to see animals widely mistreated in Israel. She decided it was high time to address the problem—and that has made a world of difference.